By Martin Vogel

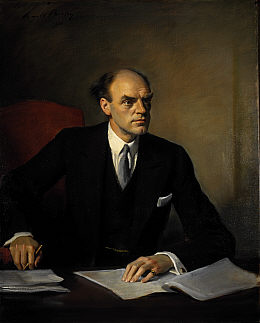

Goodness gracious, what would Reith have thought?

Lord Reith, the founder of the BBC, would certainly not have shared the bemusement that many have felt at the extent of media coverage and public outrage focussed on the Sachsgate scandal. He would have viscerally appreciated why the national conversation has been dominated by reaction to two boorish entertainers, handsomely paid by the public purse, using the public airwaves to humiliate a young woman in obscene phone calls to her grandfather, a much-loved actor.

The clarity of Reith’s original mission for the BBC to inform, educate and entertain pointed to some degree of moral purpose which still shapes people’s expectations of the organisation. Since the last renewal of the BBC’s charter at the beginning of 2007, the Reithian mission has given way to six, rather more mushy, “public purposes“. These could justify almost any activity the BBC chooses to undertake – and, inside the BBC, they do, if we are to judge by Russell Brand’s and Jonathan Ross’s antics and the tardiness of the management’s response.

What is strange is that this is still the case, given everything that has happened in recent years: Hutton, Queengate and the phone-in scandals. Last week’s events are an object lesson in how an organisation in reputational crisis fails to learn the lessons of its previous mistakes. Banks, take note.

The first point to make is that the BBC is increasingly suffering the downside of its own twin-strategy of expansion of services and pursuit of younger audiences. Its reputation was built on years of careful programming characterised by high craft skills and uncompromising editorial standards. The rapid expansion of services that began in the mid-1990s necessitated three developments which would undermine these foundations: the loss of experienced but expensive older staff to create the savings to invest in new services; the rapid intake of inexperienced younger staff to produce the content for the new services; and management spreading itself too thinly to be able adequately to oversee the exponentially greater volume of output. To put it more simply, the culture walked out the door at just the time that it needed to communicate itself to a new cadre of producers.

If you combine this with the pursuit of younger audiences, it begins to create an explosive cocktail. As in the banking sector, time-worn managers began to sanction risks they didn’t fully comprehend as producers were encouraged to innovate and make the BBC relevant to audiences who were left cold by its traditional values. If managers were fully across the output at all, they were inhibited from reigning in edgy, blokey or even offensive content on the grounds that their sensibilities were a poor basis on which to evaluate programmes aimed at the elusive youth audience. Somewhere along the way, the Reithian vision of raising the horizons of the BBC’s audiences gave way to appeasing the tastes of promiscuous media consumers who would find what they wanted elsewhere if the BBC didn’t give it to them.

The second point is that this was and remains a systemic crisis in a way that the Director-General, Mark Thompson, seems unwilling to acknowledge. In an interview last week, he blamed the affair on misjudgments by individuals:

“What our investigation of this incident suggests is not a failure of our systems. But, I’m afraid, our systems rely across the BBC on the judgment of programme editors, executive editors and producers who are deciding in the context of our guidelines, in the context of our compliance processes, what should be broadcast. This was a failure of judgment.”

So it’s all the fault of the people on the front line. This is the same mindset that last year created a massive training initiative for all BBC editorial staff in response to the trust scandals, and did the same before that following the Hutton inquiry. The mindset emphasises procedures and compliance. But it fails to take into account that the culture transmits more powerfully that compliance is trumped by indulging talent and testing standards in pursuit of audience share.

The cost and power of on-air talent – particularly big name celebrities like Jonathan Ross – is intimidating to inexperienced producers, who can’t be sure that their managers will support them if they cross the stars. As the presenter Paul Gambaccini has revealed, Lesley Douglas, the ex-Radio 2 controller, had a reputation for letting Russell Brand do anything. So who on her team would have been able to manage him? Certainly not a 25-year-old producer who worked for his company.

What seems to be happening at the BBC is that the leadership is allowing a culture to flourish which is misaligned with the official values. The massive training programmes fail to address this. They simply restate official values, which everybody knows already, but don’t get to grips with the real tensions between following procedures and gaining audience share. What is lacking is a leadership which cascades the values in a meaningful sense in the day-to-day realities of making programmes.

A third and final point relates to the fig leaf of “edgy” comedy. This, in some ways, relates to engaging younger audiences but goes far beyond that. Ross and Brand on Radio 2 were addressing the middle-aged and are part of a more general drive to keep the output fresh, in line with modern sensibilities. BBC executives, commentators and entertainers have been queueing up to express concern that creative production should not be allowed to lose its capacity to take risks. But the reaction to Ross and Brand suggests that modern sensibilities are not as coarse as media executives have been imagining. Last week’s surge of participation in the sport of complaining to Ofcom points to significant pent-up dislike of the Ross brand of entertainment (and possibly resentment at its high cost to the licence payer).

The broader point is that the halo of creative risk really doesn’t apply to this case. There is a world of difference between gratuitous bullying of an old man and the carefully calibrated wit of, say, The Thick of It. Everyone – producers, compliance officers and the audience – understands the difference. There’s no reason why this episode should stifle genuine creativity elsewhere. But it might be no bad thing if last week’s tumult caused the BBC to tread with more care and creative diversity – a point noted by Ian Jack (who saw in Russell Brand an exemplar of the Hobbesian view of humour as only ever boosting self-esteem at the expense of the less fortunate):

“Mark Thompson and other BBC voices this week talked as though comedy had always depended on its “edginess” for its creativity; the days of Chaplin, the Marx Brothers and Dad’s Army might never have been. That view is as narrow as Hobbes’s. Worse, at least for the future of the world’s greatest public-funded broadcaster, is that edginess depends on the continual finding of new edges, breaking taboos and conventions that comprise ethical standards, which, however much they vary between generations, most of us hope will always be there.”

While the events of Sachsgate may not in themselves precipitate a chill in the creative climate, it is possible that they are symptomatic of a significant change in the zeitgeist which may already be under way. One in which the public, as ever, are ahead of the media. Perhaps people are weary of excess and self-indulgence – in culture as much as in the economy. On the day that America has elected Barack Obama as its president, the laddish mean-spiritedness which is the stock in trade of the likes of Jonathan Ross and Russell Brand seems oddly out of place with the waves of dignity, optimism and change that are sweeping across the Atlantic.

Moral purpose is back in fashion and audiences want the media to fall into line. Reith would approve.