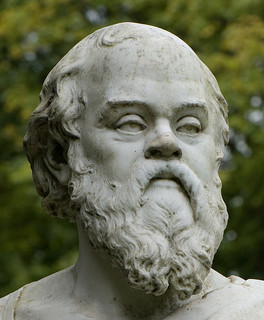

Ever since the ancient Greeks, self-awareness has been a central theme of Western philosophy and literature and there’s now scientific evidence to show that it’s essential to human health and flourishing. Recent corporate reputational crises suggest that we should now apply this understanding to organisations as much as individuals.

It seems that no organisation’s reputation is safe these days, however highly regarded it may be. Recent reputational crises have come about under the watchful – and often judgemental – eye of the media which now seems embroiled in a crisis of its own with current allegations of ‘phone-hacking at News of the World.

The response to corporate reputation-shredding varies from heads rolling and internal inquiries to calls for structural and regulatory reform of whole industries, as with banking. Any and all of this may well have its place but in the end no reform, however radical, is likely to have impact unless organisations ask some fundamental questions about their values and core purpose and how these are expressed in practice. Whenever reputational damage occurs it’s usually because there’s been some critical break in the link between stated values and behaviour. And that can only be because either there is knowing hypocrisy being practised or – much more likely – because in some key sense the organisation has lost its way and lost its sense of its true self.

The pressures on modern organisations are unprecedented, whether they are commercial, public sector or not-for-profit. Where commercial organisations experience the competitive intensity of an increasingly globalised market and all the glittering opportunities that affords, public sector organisations exist in a consumer-oriented culture where funding is increasingly linked to results, the measures of which are manifold and prone to perverse incentives. Against this backdrop it’s all too easy to see how the pressure to respond to external forces can lead to a loss of organisational integrity.

Gillian Tett’s wonderfully readable account of the 2008 financial crisis Fools’ Gold provides a compelling illustration of precisely this point. It tells the story of JPMorgan, one of the few Wall Street investment banks that emerged from the crash with its reputation intact, albeit as part of JPMorgan Chase.

Tett is criticised by some for being too favourable in her treatment of the bank. After all, it was its employees whose innovations fuelled the boom in securitised debt and credit derivatives that were the ultimate cause of the crash. The same critics find it hard to accept the arguments of those who created these products and who claim not to have foreseen the bad ends to which they would be put by others. What is beyond doubt however is that JP Morgan resolutely resisted any significant use of them to repackage mortgage debt or “sub-prime”. It paid a heavy price for not doing so, falling behind its competitors and succumbing to not one but two mergers as its performance relative to others deteriorated. And yet, despite this, what comes through in Tett’s account is a business that had such a strong corporate culture that it could withstand such intense, external pressure. Long seen as blue-blooded and conservative in its ways, JPMorgan’s culture, as described by Tett, was one that prided itself on the wider, social factors in deal-making such as long-term client relationships, loyalty and reputation. Part of this mix was a deeply instilled and cautious attitude to risk which ultimately proved the bank’s salvation. To have behaved as other banks did with regard to “sub-prime” would, it seems, have been a betrayal of the bank’s core principles in the interests of short-term gain.

Put another way, JPMorgan seems to have had a high degree of corporate self-knowledge. Self-knowledge has been a preoccupation of Western philosophy and literature for millennia and has always been regarded as essential to what Greek philosophers saw as the “good life” – a life that is not just enjoyable and fulfilling but one that is principled and morally scrupulous as well. More than that, the “good life” is enjoyable and fulfilling precisely because it has this principled quality about it. To know ourselves is to see ourselves as we really and to understand our essential connectedness to others as well. As both Greek and Shakespearean tragedy show us, bad things happen when we lack self-knowledge. The Greeks called this “hubris” – the pride or arrogance that comes when we lose touch with reality and begin to over-estimate our own competence or capabilities.

In the mid 90s Daniel Goleman drew together recent findings in psychology and neuro-science to show how “emotional intelligence” was a far greater driver of personal performance and effectiveness than the business world had hitherto appreciated. At the heart of “emotional intelligence” lies the concept of self-knowledge that the ancients knew so well. Goleman’s work – and that of many others – spawned a whole new approach to leadership and how individuals at all levels in organisations should exercise it. However, recent reputational crises suggest that organisations no less than individuals need to exercise self-awareness. For organisations are in reality organisms – entities that have a life and character that is greater than the sum of the individuals who work for them and yet which are wholly dependent on the probity and effectiveness of those individuals. Is an organisation’s sole purpose to make money for its employees and shareholders? Or does it have a goal that serves the interests of both its customers and of society more widely as well? On these questions, and – crucially – the extent to which organisations provide answers in their actions, hang the whole issue of corporate reputation. As Socrates is reported to have said well over two thousand years ago:

“The way to gain a good reputation is to endeavour to be what you desire to appear”

Image courtesy Ben Crowe.